|

|

| Line 240: |

Line 240: |

| | | | |

| | The input language can be set via the command line | | The input language can be set via the command line |

| − |

| |

| − | =CVC4's native input language=

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The native input language consists of a sequence of symbol declarations and commands, each followed by a semicolon (<code>;</code>).

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Any text after the first occurrence of a percent character and to the end of the current line is a comment:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | %%% This is a native language comment

| |

| − |

| |

| − | == Type System ==

| |

| − |

| |

| − | CVC4's type system includes a set of built-in types which can be expanded with additional user-defined types.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The type system consists of ''first-order'' types, ''subtypes'' of first-order types, and ''higher-order'' types, all of which are interpreted as sets.

| |

| − | For convenience, we will sometimes identify below the interpretation of a type with the type itself.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | First-order types consist of basic types and structured types. The basic types are <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>, <math>\mathrm{REAL}</math>, <math>\mathrm{BITVECTOR}(n)</math> for all <math>n > 0</math>, as well as user-defined basic types (also called uninterpreted types).

| |

| − | The structured types are array, tuple, record types, and ML-style user-defined (inductive) datatypes.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''Note:''' Currently, subtypes consist only of the built-in subtype <math>\mathrm{INT}</math> of <math>\mathrm{REAL}</math>.

| |

| − | <!-- and are covered in the [[#Subtypes|Subtypes]] section. -->

| |

| − | Support for CVC3-style user-defined subtypes will be added in a later release.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Function types are the only higher-order types.

| |

| − | More precisely, they are just second-order types

| |

| − | since function symbols in CVC4, both built-in and user-defined, can take as argument or return only values of

| |

| − | a first-order type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Basic Types ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== The BOOLEAN Type ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math> type is interpreted as the two-element set of Boolean values

| |

| − | <math>\{\mathrm{TRUE},\; \mathrm{FALSE}\}</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''Note:''' CVC4's treatment of this type differs from CVC3's where <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math> is used only as the type of formulas, but not as value type. CVC3 follows the two-tiered structure of classical first-order logic

| |

| − | which distinguishes between formulas and terms, and allows terms to occur in formulas but not vice versa (with the exception of the IF-THEN-ELSE construct).

| |

| − | CVC4 drops the distinction between terms and formulas and defines the latter just as terms of type <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>. As such, formulas can occur as subterms of possibly non-Boolean terms.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Example:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [To do]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== The REAL Type ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The <math>\mathrm{REAL}</math> type is interpreted as the set of real numbers.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that these are the (infinite precision) mathematical reals,

| |

| − | not the floating point numbers.

| |

| − | Support for floating point types is planned for future versions.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x, y : REAL;

| |

| − | QUERY (( x <= y ) AND ( y <= x )) => ( x = y );

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== The INT Type ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The <math>\mathrm{INT}</math> type is interpreted as the set of integer numbers

| |

| − | and is considered as a subtype of <math>\mathrm{REAL}</math>.

| |

| − | The latter means in particular that it is possible to mix integer and real terms

| |

| − | in expressions without the need of an explicit ''upcasting'' operator.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that these are the (infinite precision) mathematical integers,

| |

| − | not the finite precision machine integers used in most programming languages.

| |

| − | The latter are models by [[ #Bitvectors | bit vector ]] types.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x, y : INT;

| |

| − | QUERY ((2 * x + 4 * y <= 1) AND ( y >= x)) => (x <= 0);

| |

| − | z : REAL;

| |

| − | QUERY (2 * x + z <= 3.5) AND (z >= 1);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== Bit Vector Types ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | For every positive integer <math>n</math>, the type <math>\mathrm{BITVECTOR}(n)</math> is interpreted as the set of all bit vectors of size <math>n</math>.

| |

| − | A rich set of bit vector operators is supported.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== User-defined Basic Types ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Users can define new basic types

| |

| − | (often referred to as ''uninterpreted'' types in the SMT literature).

| |

| − | Each such type is interpreted as a set of unspecified cardinality

| |

| − | but disjoint from any other type.

| |

| − | <!--

| |

| − | Can we specify cardinalities?

| |

| − | -->

| |

| − | User-defined basic types are created by declarations like the following:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % User declarations of basic types:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | MyBrandNewType: TYPE;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Apples, Oranges: TYPE;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Structured Types ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | CVC4's structured types are divided in the following families.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== Array Types ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Array types are created by the mixfix type constructors <math>\mathrm{ARRAY}\ \_\ \mathrm{OF}\ \_</math>

| |

| − | whose arguments can be instantiated by any value type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | I : TYPE;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | %% Array types:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Arrays with indices from I and values from REAL

| |

| − | Array1: TYPE = ARRAY I OF REAL;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Arrays with integer indices and array values

| |

| − | Array2: TYPE = ARRAY INT OF (ARRAY INT OF REAL);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Arrays with integer pair indices and integer values

| |

| − | IntMatrix: TYPE = ARRAY [INT, INT] OF INT;

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | An array type of the form <math>\mathrm{ARRAY}\ T_1\ \mathrm{OF}\ T_2</math> is interpreted

| |

| − | as the set of all total maps from <math>T_1</math> to <math>T_2</math>.

| |

| − | The main difference with the function type <math>T_1 \to T_2</math> is that arrays,

| |

| − | contrary to functions, are first-class objects of the language, that is, values of an array

| |

| − | type can be arguments or results of functions.

| |

| − | Furthermore, array types come equipped with an update operation.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== Tuple Types ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Tuple types are created by the mixfix type constructors

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \begin{array}{l} [\ \_\ ] \\[1ex] [\ \_\ ,\ \_\ ] \\[1ex] [\ \_\ ,\ \_\ \ ,\ \_\ ] \\[1ex] \ldots \end{array}

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | whose arguments can be instantiated by any value type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | IntArray: TYPE = ARRAY INT OF INT;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Tuple type declarations

| |

| − |

| |

| − | RealPair: TYPE = [REAL, REAL]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | MyTuple: TYPE = [ REAL, IntArray, [INT, INT] ];

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A tuple type of the form <math>[T_1, \ldots, T_n]</math> is interpreted

| |

| − | as the Cartesian product <math>T_1 \times \cdots \times T_n</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that while the types <math>(T_1, \ldots, T_n) \to T</math> and

| |

| − | <math>[T_1 \times \cdots \times T_n] \to T</math> are semantically equivalent,

| |

| − | they are operationally different in CVC4.

| |

| − | The first is the type of functions that take <math>n</math> arguments

| |

| − | of respective type <math>T_1</math>, <math>\ldots</math>, <math>T_n</math>,

| |

| − | while the second is the type of functions that take one argument of an <math>n</math>-tuple type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== Record Types ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Similar to, but more general than tuple types, record types are created by type constructors of the form

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | [\#\ l_1: \_\ ,\ \ldots\ ,\ l_n: \_\ \#]

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | where <math>n > 0</math>, <math>l_1,\ldots, l_n</math> are field labels,

| |

| − | and the arguments can be instantiated with any first-order types.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | MyType: TYPE;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Record declaration

| |

| − |

| |

| − | RecordType: TYPE = [# id: REAL, age: INT, info: MyType #];

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The order of the fields in a record type is meaningful:

| |

| − | permuting the field names gives a different type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that record types are non-recursive.

| |

| − | For instance, it is not possible to declare a record type called <code>Person</code> containing

| |

| − | a field of type <code>Person</code>.

| |

| − | Recursive types are provided in CVC4 by the more general inductive data types.

| |

| − | (As a matter of fact, both record and tuple types are implemented internally as inductive data types.)

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== Inductive Data Types ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Inductive data types in CVC4 are similar to inductive data types of functional languages.

| |

| − | They can be parametric or not.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ===== Non-Parametric Data Types =====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Non-parametric data types are created by declarations of the form

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \begin{array}{l}

| |

| − | \mathrm{DATATYPE} \\

| |

| − | \begin{array}{ccc}

| |

| − | \ \ A_1 & = & C_{1,1} \mid C_{1,2} \mid \cdots \mid C_{1,m_1}, \\

| |

| − | \ \ A_2 & = & C_{2,1} \mid C_{2,2} \mid \cdots \mid C_{2,m_2}, \\

| |

| − | \ \ \vdots & = & \vdots \\

| |

| − | \ \ A_n & = & C_{n,1} \mid C_{n,2} \mid \cdots \mid C_{n,m_n} \\

| |

| − | \end{array}

| |

| − | \\

| |

| − | \mathrm{END};

| |

| − | \end{array}

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − | where

| |

| − | each <math>A_i</math> is a type name and

| |

| − | each <math>C_{ij}</math> is either a constant symbol or an expression of the form

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>\mathit{cons}(\ \mathit{sel}_1: T_1,\ \ldots,\ \mathit{sel}_k: T_k\ )

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − | where <math>T_1, \ldots, T_k</math> are any first-order types, including any <math>A_i</math>.

| |

| − | Such declarations define the data types <math>A_1, \ldots, A_n</math>.

| |

| − | For each data type <math>A_i</math> they introduce:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | * constructor symbols <math>cons</math> of type <math>(T_1, \ldots, T_k) \to \mathit{type\_name}_i</math>,

| |

| − | * selector symbols <math>\mathit{sel}_j</math> of type <math>\mathit{type\_name}_i \to T_j</math>, and

| |

| − | * tester symbols <math>\mathit{is\_cons}</math> of type <math>\mathit{type\_name}_i \to \mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that permitting more than one data type to be defined in the same declarations allows

| |

| − | the definition of mutually recursive types.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % simple enumeration type

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % implicitly defined are the testers: is_red, is_yellow and is_blue

| |

| − | % (similarly for the other data types)

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE

| |

| − | PrimaryColor = red | yellow | blue

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % infinite set of pairwise distinct values ..., v(-1), v(0), v(1), ...

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE

| |

| − | Id = v (id: INT)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % ML-style integer lists

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE

| |

| − | IntList = nil | ins (head: INT, tail: IntList)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % AST for lamba calculus

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE

| |

| − | Term = var (index: INT)

| |

| − | | apply (arg_1: Term, arg_2: Term)

| |

| − | | lambda (arg: INT, body: Term)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Trees

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE

| |

| − | Tree = tree (value: REAL, children: TreeList),

| |

| − | TreeList = nil_tl

| |

| − | | ins_tl (first_t1: Tree, rest_t1: TreeList)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Constructor, selector and tester symbols defined for a data type have global scope.

| |

| − | So, for example, it is not possible for two different data types to use

| |

| − | the same name for a constructor.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | An inductive data type is interpreted as a term algebra constructed by the constructor symbols

| |

| − | over some sets of generators.

| |

| − | For example, the type <code>IntList</code> defined above is interpreted as the set

| |

| − | of all terms constructed with <code>nil</code> and <code>ins</code> over the integers.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ===== Parametric Data Types =====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Parametric data types are infinite families of (non-parametric) data types

| |

| − | with each family parametrized by one or more type variables.

| |

| − | They are created by declarations of the form

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \begin{array}{l}

| |

| − | \mathrm{DATATYPE} \\

| |

| − | \begin{array}{ccc}

| |

| − | \ \ A_1[X_{1,1}, \ldots, X_{1,p_1}] & = & C_{1,1} \mid C_{1,2} \mid \cdots \mid C_{1,m_1}, \\

| |

| − | \ \ A_2[X_{2,1}, \ldots, X_{2,p_2}] & = & C_{2,1} \mid C_{2,2} \mid \cdots \mid C_{2,m_2}, \\

| |

| − | \ \ \vdots & = & \vdots \\

| |

| − | \ \ A_n[X_{n,1}, \ldots, X_{n,p_n}] & = & C_{n,1} \mid C_{n,2} \mid \cdots \mid C_{n,m_n} \\

| |

| − | \end{array}

| |

| − | \\

| |

| − | \mathrm{END};

| |

| − | \end{array}

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − | where

| |

| − | each <math>A_i</math> is a type name parametrized by the type variables <math>X_{i,1}, \ldots, X_{i,p_i}</math>

| |

| − | and

| |

| − | each <math>C_{ij}</math> is either a constant symbol or an expression of the form

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>\mathit{cons}(\ \mathit{sel}_1: T_1,\ \ldots,\ \mathit{sel}_k: T_k\ )

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − | where <math>T_1, \ldots, T_k</math> are any first-order types,

| |

| − | possibly parametrized by <math>X_1, \ldots, X_p</math>, including any <math>A_i</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Parametric pairs

| |

| − | DATATYPE [X, Y]

| |

| − | Pair[X, Y] = pair (first: X, second: Y)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Parametric lists

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE [X]

| |

| − | List[X] = nil | cons (head: X, tail: List[X])

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Parametric trees using the list type above

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE [X]

| |

| − | Tree[X] = node (value: X, children: List[Tree[X]]),

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The declarations above define infinitely many types of the form

| |

| − | Pair[S,T], List[T] and Tree[T] where S and T are first-order types.

| |

| − | Note that the identifier <code>List</code> above, for example, by itself does not denote a type.

| |

| − | In contrast, the terms <code>List[Real]</code>, <code>List[List[Real]]</code>, <code>List[Tree[INT]]</code>,

| |

| − | and so on do.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ===== Restriction to Inductive Types =====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | By adopting a term algebra semantics, CVC4 allows only ''inductive'' data types,

| |

| − | that is, data types whose values are essentially (labeled, ordered) finite trees.

| |

| − | Infinite structures such as streams or even finite but cyclic ones

| |

| − | such as circular lists are then excluded.

| |

| − | For instance, none of the following declarations define inductive data types,

| |

| − | and are rejected by CVC4:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE

| |

| − | IntStream = s (first:INT, rest: IntStream)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE

| |

| − | RationalTree = node1 (child: RationalTree)

| |

| − | | node2 (left_child: RationalTree, right_child:RationalTree)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE

| |

| − | T1 = c1 (s1: T2),

| |

| − | T2 = c2 (s2: T1)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In concrete, a declaration of <math>n \geq 1</math> datatypes <math>T_1, \ldots, T_n</math> will be rejected if for any one of the types <math>T_1, \ldots, T_n</math>, it is impossible to build a finite term of that type using only the constructors of <math>T_1, \ldots, T_n</math> and free constants of type other than <math>T_1, \ldots, T_n</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Inductive data types are the only types where the user also chooses names for the built-in operations to:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | * construct a value of the type (with the constructors),

| |

| − | * extract components from a value (with the selectors), or

| |

| − | * check if a value was constructed with a certain constructor or not (with the testers).

| |

| − |

| |

| − | For all the other types, CVC4 provides predefined names for the built-in operations on the type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Function Types ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Function (<math>\to</math>) types are created by the mixfix type constructors

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \begin{array}{l}

| |

| − | \_ \to \_ \\[1ex] (\ \_\ ,\ \_\ ) \to \_

| |

| − | \\[1ex] (\ \_\ ,\ \_\ ,\ \_\ ) \to \_

| |

| − | \\[1ex] \ldots

| |

| − | \end{array}

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − | whose arguments can be instantiated by any first-order type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Function type declarations

| |

| − |

| |

| − | UnaryFunType: TYPE = INT -> REAL;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | BinaryFunType: TYPE = (REAL, REAL) -> ARRAY REAL OF REAL;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | TernaryFunType: TYPE = (REAL, BITVECTOR(4), INT) -> BOOLEAN;

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A function type of the form <math>(T_1, \ldots, T_n) \to T</math> with <math>n > 0</math> is interpreted as the set of all ''total'' functions from the Cartesian product <math>T_1 \times \cdots \times T_n</math> to <math>T</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The example above also shows how to introduce type names.

| |

| − | A name like <code>UnaryFunType</code> above is just an abbreviation for the type <math>\mathrm{INT} \to \mathrm{REAL}</math> and can be used interchangeably with it.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In general, any type defined by a type expression <code>E</code> can be given a name with the declaration:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | name : TYPE = E;

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Type Checking ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In CVC4, formulas and terms are statically typed at the level of types

| |

| − | (as opposed to subtypes) according to the usual rules of first-order many-sorted logic,

| |

| − | with the main difference that formulas are just terms of type <math>BOOLEAN</math>:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | * each variable has one associated first-order type,

| |

| − | * each constant symbol has one or more associated first-order types,

| |

| − | * each function symbol has one or more associated function types,

| |

| − | * the type of a term consisting just of a variable is the type associated to that variable,

| |

| − | * the type of a term consisting just of a constant symbol is the type associated to that constant symbol,

| |

| − | * the term obtained by applying a function symbol <math>f</math> to the terms <math>t_1, \ldots, t_n</math> is <math>T</math> if <math>f</math> has type <math>(T_1, \ldots, T_n) \to T</math> and each <math>t_i</math> has type <math>T_i</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Attempting to enter an ill-typed term will result in an error.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Another significant difference with standard many-sorted logic is that

| |

| − | some built-in symbols are parametrically polymorphic.

| |

| − | For instance, the function symbol for extracting the element of any array has

| |

| − | type <math>(\mathit{ARRAY}\ T_1\ \mathit{OF}\ T_2,\; T_1) \to T_2</math>

| |

| − | for all first-order types <math>T_1, T_2</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==== Type Ascription ====

| |

| − |

| |

| − | By the type inference rules above some terms might have more than one type.

| |

| − | This can happen with terms built with polymorphic data type constructors

| |

| − | that have more than one return type for the same input type.

| |

| − | In that case, a type ascription operator (<code>::</code>) must be applied

| |

| − | to the constructor to specify the intended return type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE [X]

| |

| − | List[X] = nil | cons (head: X, tail: List[X])

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ASSERT y = cons(1, nil::List[REAL]);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | DATATYPE [X, Y]

| |

| − | Union[X, Y] = left(val_l: X) | right(val_r: Y)

| |

| − | END;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ASSERT y = left::Union[BOOLEAN, REAL](TRUE);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The constant symbol <math>\mathrm{nil}</math> declared above has infinitely many types

| |

| − | (<math>\mathrm{List}[\mathrm{REAL}]</math>, <math>\mathrm{List}[\mathrm{BOOLEAN}]</math>,

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{List}[[\mathrm{REAL}, \mathrm{REAL}]]</math>,

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{List}[\mathrm{List}[\mathrm{REAL}]]</math>, ...)

| |

| − | CVC4's type checker requires the user to indicate explicitly the type

| |

| − | of each occurrence of <code>nil</code> in a term.

| |

| − | Similarly,

| |

| − | the injection operator <code>left</code> has infinitely many return types

| |

| − | for the same input type, for instance:

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN} \to \mathrm{Union}[\mathrm{BOOLEAN}, \mathrm{REAL}]</math>,

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN} \to \mathrm{Union}[\mathrm{BOOLEAN}, [\mathrm{REAL}, \mathrm{REAL}]]</math>,

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN} \to \mathrm{Union}[\mathrm{BOOLEAN}, \mathrm{List}[\mathrm{REAL}]]</math>,

| |

| − | and so on.

| |

| − | Applications of <code>left</code> need to specify the intended returned typed, as shown above.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | == Terms and Formulas ==

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In addition to type expressions, CVC4 has expressions for terms and for formulas

| |

| − | (i.e., terms of type <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>).

| |

| − | By and large, these are standard first-order terms built out of typed variables,

| |

| − | predefined theory-specific operators, free (i.e., user-defined) function symbols,

| |

| − | and quantifiers.

| |

| − | Extensions include an if-then-else operator, lambda abstractions, and local symbol

| |

| − | declarations, as illustrated below.

| |

| − | Note that these extensions still keep CVC4's language first-order.

| |

| − | In particular, lambda abstractions are restricted to take and return only terms of

| |

| − | a first-order type.

| |

| − | Similarly, variables can only be of a first-order type.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A number of built-in function symbols (for instance, the arithmetic ones) are used

| |

| − | as infix operators. All user-defined symbols are used as prefix ones.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | User-defined, i.e., free, function symbols include ''constant symbols'' and

| |

| − | ''predicate symbols'', respectively nullary function symbols and function symbols

| |

| − | with a <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math> return type.

| |

| − | These symbols are introduced with global declarations of the form

| |

| − | <math> f_1, \ldots, f_m: T;</math>

| |

| − | where <math>m > 0</math>, <math>f_i</math> are the names of the symbols and

| |

| − | <math>T</math> is their type:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % integer constants

| |

| − |

| |

| − | a, b, c: INT;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % real constants

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x, y, z: REAL;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % unary function

| |

| − |

| |

| − | f1: REAL -> REAL;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % binary function

| |

| − |

| |

| − | f2: (REAL, INT) -> REAL;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % unary function with a tuple argument

| |

| − |

| |

| − | f3: [INT, REAL] -> BOOLEAN;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % binary predicate

| |

| − |

| |

| − | p: (INT, REAL) -> BOOLEAN;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Propositional "variables"

| |

| − |

| |

| − | P, Q; BOOLEAN;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Like type declarations, function symbol declarations like the above have global scope

| |

| − | and must be unique.

| |

| − | In other words, it is not possible to declare a function symbol globally more than once

| |

| − | in the same lexical scope.

| |

| − | This entails among other things that globally-defined free symbols cannot be overloaded

| |

| − | with different types and that theory symbols cannot be redeclared globally as free symbols.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Global symbol definitions ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | As with types, a function symbol can be defined as the name of another term

| |

| − | of the corresponding type.

| |

| − | With constant symbols, this is done with a declaration of the form <math>f:T = t;</math> :

| |

| − |

| |

| − | c: INT;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | i: INT = 5 + 3*c; % i is effectively a shorthand for 5 + 3*c

| |

| − |

| |

| − | j: REAL = 3/4;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | t: [REAL, INT] = (2/3, -4);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | r: [# key: INT, value: REAL #] = (# key := 4, value := (c + 1)/2 #);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | f: BOOLEAN = FORALL (x:INT): x <= 0 OR x > c ;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A restriction on constants of type <math>\mathit{BOOLEAN}</math> is that their value

| |

| − | can only be a closed formula, that is, a formula with no free variables.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A term and its name can be used interchangeably in later expressions.

| |

| − | Named terms are often useful for shared subterms (terms used several times in different places)

| |

| − | since their use can make the input exponentially more concise.

| |

| − | Named terms are processed very efficiently by CVC4.

| |

| − | It is much more efficient to associate a complex term with a name directly rather than

| |

| − | to declare a constant and later assert that it is equal to the same term.

| |

| − | This point is explained in more detail later in section [[Commands | Commands]].

| |

| − |

| |

| − | More generally, in CVC4 one can associate a term to function symbols of any arity.

| |

| − | For non-constant function symbols this is done with a declaration of the form

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>f:(T_1, \ldots, T_n) \to T = \mathrm{LAMBDA}(x_1:T_1, \ldots, x:T_n): t\;;</math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | where <math>t</math> is any term of type <math>T</math> with free variables

| |

| − | in <math>\{x_1, \ldots, x_n\}</math>.

| |

| − | The lambda binder has the usual semantics and conforms to the usual lexical scoping rules:

| |

| − | within the term <math>t</math> the declaration of the symbols <math>x_1, \ldots, x_n</math>

| |

| − | as local variables of respective type <math>T_1, \ldots, T_n</math> hides any previous

| |

| − | declarations of those symbols that are in scope.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | As a general shorthand, when <math>k</math> consecutive types

| |

| − | <math>T_i, \ldots, T_{i+k-1}</math> in the lambda expression

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{LAMBDA}(x_1:T_1, \ldots, x:T_n): t</math> are identical, the syntax

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{LAMBDA}(x_1:T_1, \ldots, x_i,\ldots, x_{i+k-1}:T_i,\ldots, x:T_n): t</math>

| |

| − | can also be used.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Global declaration of x as a unary function symbol

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x: REAL -> REAL;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Local declarations of x as variable (hiding the global one)

| |

| − |

| |

| − | f: REAL -> REAL = LAMBDA (x: REAL): 2*x + 3;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | p: (INT, INT) -> BOOLEAN = LAMBDA (x,i: INT): i*x - 1 > 0;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | g: (REAL, INT) -> [REAL, INT] = LAMBDA (x: REAL, i:INT): (x + 1, i - 3);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that lambda definitions are not recursive:

| |

| − | the symbol being defined cannot occur in the body of the lambda term.

| |

| − | They should be understood as macros.

| |

| − | For instance, any occurrence of the term <math>f(t)</math>

| |

| − | where <math>f</math> is as defined above will be treated

| |

| − | as if it was the term <math>(2*t + 3)</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Local symbol definitions ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Constant and function symbols can also be declared locally anywhere within a term

| |

| − | by means of a let binder.

| |

| − | This is done with a declaration of the form

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \mathrm{LET}\ f = t \ \mathrm{IN}\ t' ;

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | where <math>t</math> is a term with no free variables, possibly a lambda term.

| |

| − | Let binders can be nested arbitrarily and follow the usual lexical scoping rules.

| |

| − | The following general form

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \mathrm{LET}\ f_1 = t_1, f_2 = t_2, \ldots, f_n = t_m \ \mathrm{IN}\ t ;

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − | can be use above can used as a shorthand for

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \mathrm{LET}\ f_1 = t_1\ \mathrm{IN}\

| |

| − | \mathrm{LET}\ f_2 = t_2\ \mathrm{IN}\

| |

| − | \ldots \

| |

| − | \mathrm{LET}\ f_n = t_m \ \mathrm{IN}\ t ;

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | t: REAL =

| |

| − | LET x1 = 42,

| |

| − | g = LAMBDA(x:INT): x + 1,

| |

| − | x2 = 2*x1 + 7/2

| |

| − | IN

| |

| − | (LET x3 = g(x1) IN x3 + x2) / x1;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that the same symbol = is used, unambiguously, in the syntax of global declarations,

| |

| − | let declarations, and as a predicate symbol.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''Note:'''

| |

| − | A <math>\mathrm{LET}</math> term with a multiple symbols defines them sequentially.

| |

| − | A parallel version of the <math>\mathrm{LET}</math> construct will be introduced in a later version.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | == Built-in theories and their symbols ==

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In addition to user-defined symbols, CVC4 terms can use a number of predefined symbols:

| |

| − | the logical symbols, such as <math>\mathrm{AND}</math>, <math>\mathrm{OR}</math>, etc.,

| |

| − | as well as theory symbols, function symbols belonging to one of the built-in theories.

| |

| − | They are described next, with the theory symbols grouped by theory.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Logical Symbols ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The logical symbols in CVC4's language include

| |

| − | the equality and disequality predicate symbols, respectively written as = and /=,

| |

| − | the multiarity disequality symbol <math>\mathrm{DISTINCT}</math>,

| |

| − | together with the logical constants <math>\mathrm{TRUE}</math>, <math>\mathrm{FALSE}</math>,

| |

| − | the connectives <math>\mathrm{NOT}</math>, <math>\mathrm{AND}</math>, <math>\mathrm{OR}</math>, <math>\mathrm{XOR}</math>, <math>\Rightarrow</math>, <math>\Leftrightarrow</math>, and

| |

| − | the first-order quantifiers <math>\mathrm{EXISTS}</math> and <math>\mathrm{FORALL}</math>,

| |

| − | all with the standard many-sorted logic semantics.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The binary connectives have infix syntax and type

| |

| − | <math>(\mathrm{BOOLEAN},\mathrm{BOOLEAN}) \to \mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>.

| |

| − | The symbols = and /=, which are also infix, are instead parametrically polymorphic,

| |

| − | having type <math>(T,T) \to \mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>

| |

| − | for every first-order type <math>T</math>.

| |

| − | They are interpreted respectively as the identity relation and its complement.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The DISTINCT symbol is both overloaded and polymorphic.

| |

| − | It has type <math>(T,...,T) \to \mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>

| |

| − | for every sequence <math>(T,...,T)</math> of length <math>n > 0</math>

| |

| − | and first-order type <math>T</math>.

| |

| − | For each <math>n > 0</math>, it is interpreted as the relation

| |

| − | that holds exactly for tuples of pairwise distinct elements.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The syntax for quantifiers is similar to that of the lambda binder.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Here is an example of a formula built just of these logical symbols and variables:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A, B: TYPE;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | q: BOOLEAN = FORALL (x,y: A, i,j,k: B):

| |

| − | i = j AND i /= k => EXISTS (z: A): x /= z OR z /= y;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Binding and scoping of quantified variables follows the same rules as

| |

| − | in let expressions.

| |

| − | In particular, a quantifier will shadow in its scope any constant and function symbols

| |

| − | with the same name as one of the variables it quantifies:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A: TYPE;

| |

| − | i, j: INT;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % The first occurrence of i and of j in f are constant symbols,

| |

| − | % the others are variables.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | f: BOOLEAN = i = j AND FORALL (i,j: A): i = j OR i /= j;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Optionally, it is also possible to specify instantiation patterns

| |

| − | for quantified variables.

| |

| − | The general syntax for a quantified formula <math>\psi</math> with patterns is

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | Q\;(x_1:T_1, \ldots, x_k:T_k):\; p_1: \ldots\; p_n:\; \varphi

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | where <math>n \geq 0</math>, <math>Q</math> is

| |

| − | either <math>\mathrm{FORALL}</math> or <math>\mathrm{EXISTS}</math>,

| |

| − | <math>\varphi</math> is a term of type <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>,

| |

| − | and each of the <math>p_i</math>'s,

| |

| − | a pattern for the quantifier <math>Q\;(x_1:T_1, \ldots, x_k:T_k)</math>, has the form

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \mathrm{PATTERN}\; (t_1, \ldots, t_m)

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | where <math>m > 0</math> and <math>t_1, \ldots, t_m</math> are

| |

| − | arbitrary binder-free terms (no lets, no quantifiers).

| |

| − | Those terms can contain (free) variables, typically, but not exclusively,

| |

| − | drawn from <math>x_1, \ldots, x_k</math>.

| |

| − | (Additional variables can occur if <math>\psi</math> occurs in a bigger formula

| |

| − | binding those variables.)

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A: TYPE;

| |

| − | b, c: A;

| |

| − | p, q: A -> BOOLEAN;

| |

| − | r: (A, A) -> BOOLEAN;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ASSERT FORALL (x0, x1, x2: A):

| |

| − | PATTERN (r(x0, x1), r(x1, x2)):

| |

| − | (r(x0, x1) AND r(x1, x2)) => r(x0, x2) ;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ASSERT FORALL (x: A):

| |

| − | PATTERN (r(x, b)):

| |

| − | PATTERN (r(x, c)):

| |

| − | p(x) => q(x) ;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ASSERT EXISTS (y: A):

| |

| − | FORALL (x: A):

| |

| − | PATTERN (r(x, y), p(y)):

| |

| − | r(x, y) => q(x) ;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Patterns have no logical meaning:

| |

| − | adding them to a formula does not change its semantics.

| |

| − | Their purpose is purely operational, as explained in

| |

| − | the [[#Instantiation Patterns | Instantiation Patterns]] section.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In addition to these constructs, CVC4 also has a general mixfix conditional operator

| |

| − | of the form

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \mathrm{IF}\ b\ \mathrm{THEN}\ t\ \mathrm{ELSIF}\ b_1\ \mathrm{THEN}\ t_1\ \ldots\ \mathrm{ELSIF}\ b_n\ \mathrm{THEN}\ t_n\ \mathrm{ELSE}\ t_{n+1}\ \mathrm{ENDIF}

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | with <math>n \geq 0</math> where

| |

| − | <math>b, b_1, \ldots, b_n</math> are terms of type <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math> and

| |

| − | <math>t, t_1, \ldots, t_n, t_{n+1}</math> are terms of the same first-order type <math>T</math>:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Conditional term

| |

| − | x, y, z, w: REAL;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | t: REAL =

| |

| − | IF x > 0 THEN y

| |

| − | ELSIF x >= 1 THEN z

| |

| − | ELSIF x > 2 THEN w

| |

| − | ELSE 2/3 ENDIF;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === User-defined Functions and Types ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The theory of user-defined functions,also know in the SMT literature as

| |

| − | the theory ''Equality over Uninterpreted Functions'', or ''EUF'', is in effect

| |

| − | a family of theories of equality parametrized by the basic types and the free symbols

| |

| − | a user can define during a run of CVC4.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | This theory has no built-in symbols (other than the logical ones).

| |

| − | Its types consist of ''all and only'' the user-defined types.

| |

| − | Its function symbols consist of ''all and only'' the user-defined free symbols.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Arithmetic ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The real arithmetic theory has two types:

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{REAL}</math> and <math>\mathrm{INTEGER}</math>

| |

| − | with the latter a subtype of the first.

| |

| − | Its built-in symbols for the usual arithmetic constants

| |

| − | and operators over the type <math>\mathrm{REAL}</math>, each with the expected type:

| |

| − | all numerals 0, 1, ..., as well as - (both unary and binary), +, *, /, <, >, <=, >=.

| |

| − | Application of the binary symbols are in infix form.

| |

| − | Note that + is only binary, and so an expression such as +4 is ill-formed.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Rational values can be expressed in decimal or fractional format,

| |

| − | e.g., 0.1, 23.243241, 1/2, 3/4, and so on.

| |

| − | A leading 0 is mandatory for decimal numbers smaller than one

| |

| − | (e.g., the syntax .3 cannot be used as a shorthand for 0.3).

| |

| − | However, a trailing 0 is ''not'' required for decimals that are whole numbers

| |

| − | (e.g., 3. is allowed as a shorthand for 3.0).

| |

| − | The size of the numerals used in the representation of natural and rational numbers

| |

| − | is unbounded; more accurately, bounded only by the amount of available memory.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Bit vectors ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Arrays ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The theory of arrays is a parametric theory of (total) unary maps.

| |

| − | It comes equipped with mixfix polymorphic selection and update operators, respectively

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>\_[\_]</math> and <math>\_\ \mathrm{WITH}\ [\_]\ := \_</math> .

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − | The semantics of these operators is the expected one:

| |

| − | for all first-order types <math>T_1</math> and <math>T_2</math>,

| |

| − | if <math>a</math> is of type <math>\mathrm{ARRAY}\ T_1 \mathrm{OF}\ T_2</math>,

| |

| − | <math>i</math> is of type <math>T_1</math>, and

| |

| − | <math>v</math> is of type <math>T_2</math>,

| |

| − | * <math>a[i]</math> denotes the value that <math>a</math> associates to index <math>i</math>,

| |

| − | * <math>a\ \mathrm{WITH}\ [i]\ := v</math> denotes a map that associates <math>v</math> to index <math>i</math> and is otherwise identical to <math>a</math>.

| |

| − | Sequential updates can be chained with the shorthand syntax

| |

| − | <math>\_\ \mathrm{WITH}\ [\_]\ := \_, \ldots, [\_]\ := \_</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A: TYPE = ARRAY INT OF REAL;

| |

| − | a: A;

| |

| − | i: INT = 4;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % selection:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | elem: REAL = a[i];

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % update

| |

| − |

| |

| − | a1: A = a WITH [10] := 1/2;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % sequential update

| |

| − | % (syntactic sugar for (a WITH [10] := 2/3) WITH [42] := 3/2)

| |

| − |

| |

| − | a2: A = a WITH [10] := 2/3, [42] := 3/2;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Since arrays are just maps, equality between them is extensional, that is,

| |

| − | for two arrays of the same type to be different they have to map at least one

| |

| − | index to differ values.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Data types ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The theory of inductive data types is in fact a family of theories parametrized

| |

| − | by a data type declaration specifying constructors and selectors

| |

| − | for one or more user-defined data types.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | No built-in operators other than equality and disequality are provided

| |

| − | for this family in the native language.

| |

| − | Each user-provided data type declaration, however, generates constructor, selector and tester operators

| |

| − | as described in the [[#Inductive Data Types | Inductive Data Types]] section.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Tuples and Records ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Semantically both records and tuples can be seen as special instances

| |

| − | of inductive data types.

| |

| − | CVC4 implements them internally indeed as data types.

| |

| − | In essence, a record type <math>[\#\ l_0:T_0, \ldots, l_n:T_n\ \#]</math>

| |

| − | is encoded as a data type of the form

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \begin{array}{l}

| |

| − | \mathrm{DATATYPE} \\

| |

| − | \ \ \mathrm{Record} = \mathit{rec}(l_0:T_0, \ldots, l_n:T_n) \\

| |

| − | \mathrm{END};

| |

| − | \end{array}

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Tuples of length <math>n</math> are in turn special cases of records whose field names are

| |

| − | the numerals from <math>0</math> to <math>n-1</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Externally, tuples and records have their own syntax for constructor and selector operators.

| |

| − | * Records of type <math>[\#\ l_0:T_0, \ldots, l_n:T_n\ \#]</math> have the associated record constructor <math>(\#\ l_0 := \_,\; \ldots,\; l_n := \_\ \#)</math> whose arguments must be terms of type <math>T_0, \ldots, T_n</math>, respectively.

| |

| − | * Tuples of type <math>[\ T_0, \ldots, T_n\ ]</math> have the associated tuple constructor <math>(\ \_,\; \ldots,\; \_\ )</math> whose arguments must be terms of type <math>T_0, \ldots, T_n</math>, respectively.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The selector operators on records and tuples follows a dot notation syntax.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Record construction and field selection

| |

| − | Item: TYPE = [# key: INT, weight: REAL #];

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x: Item = (# key := 23, weight := 43/10 #);

| |

| − | k: INT = x.key;

| |

| − | v: REAL = x.weight;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Tuple construction and projection

| |

| − | y: [REAL, INT, REAL] = ( 4/5, 9, 11/9 );

| |

| − | first_elem: REAL = y.0;

| |

| − | third_elem: REAL = y.2;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Differently from data types, records and tuples are also provided with built-in update operators similar in syntax and semantics to the update operator for arrays.

| |

| − | More precisely, for each record type <math>[\#\ l_0:T_0, \ldots, l_n:T_n\ \#]</math> and

| |

| − | each <math>i=0, \ldots, n</math>, CVC4 provides the operator

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \_\ \mathrm{WITH}\ .l_i\ := \_

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The operator maps a record <math>r</math> of that type and a value <math>v</math>

| |

| − | of type <math>T_i</math> to the record that stores <math>v</math> in field <math>l_i</math>

| |

| − | and is otherwise identical to <math>r</math>.

| |

| − | Analogously, for each tuple type <math>[T_0, \ldots, T_n]</math> and

| |

| − | each <math>i=0, \ldots, n</math>, CVC4 provides the operator

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <center>

| |

| − | <math>

| |

| − | \_\ \mathrm{WITH}\ .i\ := \_

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | </center>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | with similar semantics.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Record updates

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Item: TYPE = [# key: INT, weight: REAL #];

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x: Item = (# key := 23, weight := 43/10 #);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x1: Item = x WITH .weight := 48;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Tuple updates

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Tup: TYPE = [REAL,INT,REAL];

| |

| − | y: Tup = ( 4/5, 9, 11/9 );

| |

| − | y1: Tup = y WITH .1 := 3;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Updates to a nested component can be combined in a single WITH operator:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Cache: TYPE = ARRAY [0..100] OF [# addr: INT, data: REAL #];

| |

| − | State: TYPE = [# pc: INT, cache: Cache #];

| |

| − |

| |

| − | s0: State;

| |

| − | s1: State = s0 WITH .cache[10].data := 2/3;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that, differently from updates on arrays, tuple and record updates are

| |

| − | just additional syntactic sugar.

| |

| − | For instance, the record <code>x1</code> and tuple <code>y1</code> defined above

| |

| − | could have been equivalently defined as follows:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Record updates

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Item: TYPE = [# key: INT, weight: REAL #];

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x: Item = (# key := 23, weight := 43/10 #);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | x1: Item = (# key := x.key, weight := 48 #);

| |

| − |

| |

| − | % Tuple updates

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Tup: TYPE = [REAL,INT,REAL];

| |

| − | y: Tup = ( 4/5, 9, 11/9 );

| |

| − | y1: Tup = ( y.0, 3, y.1 );

| |

| − |

| |

| − | == Commands ==

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In addition to declarations of types and function symbols,

| |

| − | the CVC4 native language contains the following commands:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{ASSERT}\ F</math> -- Add the formula <math>F</math> to the current logical context <math>\Gamma</math>.

| |

| − | * [[#CHECKSAT|<math>\mathrm{CHECKSAT}\ F</math>]] -- Check if the formula <math>F</math> is satisfiable in the current logical context (<math>\Gamma \not\models_T \mathrm{NOT}\ F</math>).

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{CONTINUE}</math> -- After an invalid <math>\mathrm{QUERY}</math> or satisfiable <math>\mathrm{CHECKSAT}</math>, search for a counter-example different from the current one.

| |

| − | * [[#COUNTEREXAMPLE|<math>\mathrm{COUNTEREXAMPLE}</math>]] -- After an invalid <math>\mathrm{QUERY}</math> or satisfiable <math>\mathrm{CHECKSAT}</math>, print the context that is a witness for invalidity/satisfiability.

| |

| − | * [[#COUNTERMODEL|<math>\mathrm{COUNTERMODEL}</math>]] -- After an invalid <math>\mathrm{QUERY}</math> or satisfiable <math>\mathrm{CHECKSAT}</math>, print a model that makes the formula invalid/satisfiable. The model is provided in terms of concrete values for each free symbol.

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{OPTION}\ o\ v</math> -- Set the command-line option flag <math>o</math> to value <math>v</math>. The argument <math>o</math> is provide as a string literal enclosed in double-quotes and <math>v</math> as an integer value.

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{POP}</math> -- Equivalent to <math>\mathrm{POPTO}\ 1</math>

| |

| − | * [[#POPTO|<math>\mathrm{POPTO}\ n</math>]] -- Restore the system to the state it was in right before the most recent call to <math>\mathrm{PUSH}</math> made from stack level <math>n</math>. Note that the current stack level is printed as part of the output of the <math>\mathrm{WHERE}</math> command.

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{PUSH}</math> -- Save (checkpoint) the current state of the system.

| |

| − | * [[#QUERY|<math>\mathrm{QUERY}\ F</math>]] -- Check if the formula <math>F</math> is valid in the current logical context (<math>\Gamma\models_T F</math>).

| |

| − | * [[#RESTART|<math>\mathrm{RESTART}\ F</math>]] -- After an invalid <math>\mathrm{QUERY}</math> or satisfiable <math>\mathrm{CHECKSAT}</math>, repeat the check but with the additional assumption <math>F</math> in the context.

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{PRINT}\ t</math> -- Parse and print back the term <math>t</math>.

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{TRANSFORM}\ t</math> -- Simplify the term <math>t</math> and print the result.

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{WHERE}</math> -- Print all the formulas in the current logical context <math>\Gamma</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The remaining commands take a single argument, given as a string literal enclosed in double-quotes.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{ECHO}\ s</math> -- Print string <math>s</math>

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{INCLUDE}\ f</math> -- Read commands from file <math>f</math>.

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{TRACE}\ f</math> -- Turn on tracing for the debug flag <math>f</math>.

| |

| − | * <math>\mathrm{UNTRACE}\ f</math> -- Turn off tracing for the debug flag <math>f</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Here, we explain some of the above commands in more detail.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === QUERY ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The command <math>\mathrm{QUERY}\ F</math> invokes the core functionality of CVC4 to check

| |

| − | the validity of the formula <math>F</math> with respect to the assertions made thus far,

| |

| − | which constitute the context <math>\Gamma</math>.

| |

| − | The argument <math>F</math> must be well typed term of type <math>\mathrm{BOOLEAN}</math>,

| |

| − | as described in [[#Terms and Formulas | Terms and Formulas]].

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The execution of this command always terminates and produces one of three possible answers:

| |

| − | <code>valid</code>, <code>invalid</code>, and <code>unknown</code>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | * A <code>valid</code> answer indicates that <math>\Gamma \models_T F</math>. After a query returning such an answer, the logical context <math>\Gamma</math> is exactly as it was before the query.

| |

| − | * An <code>invalid</code> answer indicates that <math>\Gamma \not\models_T F</math>, that is, there is a model of the background theory <math>T</math> that satisfies <math>\Gamma \cup \{\mathrm{NOT}\ F\}</math>. When <math>\mathrm{QUERY}\ F</math> returns <code>invalid</code>, the logical context <math>\Gamma</math> is augmented with a set <math>\Delta</math> of ground (i.e., variable-free) literals such that <math>\Gamma\cup\Delta</math> is satisfiable in <math>T</math>, but <math>\Gamma\cup\Delta\models_T \mathrm{NOT}\ F</math>. In fact, in this case <math>\Delta</math> ''propositionally entails'' <math>\mathrm{NOT}\ F</math>, in the sense that, every truth assignment to the literals of <math>\Delta</math> that satisfies <math>\Delta</math> falsifies <math>F</math>. We call the new context <math>\Gamma\cup\Delta</math> a ''counterexample'' for <math>F</math>.

| |

| − | * An <code>unknown</code> answer is similar to an <code>invalid</code> answer in that additional literals are added to the context which propositionally entail <math>\mathrm{NOT}\ F</math>. The difference in this case is that CVC4 cannot guarantee that <math>\Gamma\cup\Delta</math> is actually satisfiable in <math>T</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | CVC4 may report <code>unknown</code> when the context or the query contains

| |

| − | non-linear arithmetic terms or quantifiers.

| |

| − | In all other cases, it is expected to be sound and complete,

| |

| − | i.e., to report <code>Valid</code> if <math>\Gamma \models_T F</math>

| |

| − | and <code>Invalid</code> otherwise.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | After an <code>invalid</code> (resp. <code>unknown</code>) answer,

| |

| − | counterexamples (resp. possible counterexamples) can be obtained with

| |

| − | a <math>\mathrm{WHERE}</math>, <math>\mathrm{COUNTEREXAMPLE}</math>,

| |

| − | or <math>\mathrm{COUNTERMODEL}</math> command.

| |

| − | <!---

| |

| − | WHERE always prints out all of <math>\Gamma\cup C</math>. COUNTEREXAMPLE may sometimes be more selective, printing a subset of those formulas from the context which are sufficient for a counterexample.

| |

| − | -->

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Since the <math>\mathrm{QUERY}</math> command may modify

| |

| − | the current context, if one needs to check several formulas in a row

| |

| − | in the same context, it is a good idea to surround every

| |

| − | query by a <math>\mathrm{PUSH}</math> and <math>\mathrm{POP}</math> invocation

| |

| − | in order to preserve the context:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | PUSH;

| |

| − | QUERY <formula>;

| |

| − | POP;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === CHECKSAT ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The command <math>\mathrm{CHECKSAT}\ F</math> behaves identically

| |

| − | to <math>\mathrm{QUERY}\ \mathrm{NOT}\ F</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === RESTART ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The command <math>\mathrm{RESTART}\ F</math> can only be invoked after an invalid query.

| |

| − | For example, in an interactive setting:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | QUERY <formula>;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | CVC4> invalid

| |

| − |

| |

| − | RESTART <formula2>;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Functionally, the behavior of the above command sequence is identical to the following:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | PUSH;

| |

| − | QUERY <formula>;

| |

| − | POP;

| |

| − | ASSERT <formula2>;

| |

| − | QUERY <formula>;

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The advantage of using the <math>\mathrm{RESTART}</math> command is that

| |

| − | the first command sequence may be executed much more efficiently that the second.

| |

| − | The reason is that with <math>\mathrm{RESTART}</math> CVC4 will re-use

| |

| − | what it has learned while answering the previous query rather than starting

| |

| − | over from scratch.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === COUNTERMODEL ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [More]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === COUNTEREXAMPLE ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [More]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === POPTO ===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [More]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | == Instantiation Patterns ==

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | CVC4 processes each universally quantified formula in the current context

| |

| − | by adding instances of the formula obtained by replacing its universal variables

| |

| − | with ground terms.

| |

| − | Patterns restrict the choice of ground terms for the quantified variables,

| |

| − | with the goal of controlling the potential explosion of ground instances.

| |

| − | In essence, adding patterns to a formula is a way for the user to tell CVC4

| |

| − | to focus only on certain instances which, in the user's opinion, will be

| |

| − | most helpful during a proof.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In more detail, patterns have the following effect on formulas that are found

| |

| − | in the logical context or get added to it later while CVC4 is trying to prove

| |

| − | the validity of some formula <math>F</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | If a formula in the current context starts with an existential quantifier,

| |

| − | CVC4 ''Skolemizes'' it, that is, replaces it in the context with the formula

| |

| − | obtained by substituting the existentially quantified variables

| |

| − | by fresh constants and dropping the quantifier.

| |

| − | Any patterns for the existential quantifier are simply ignored.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | If a formula starts with a universal quantifier

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{FORALL}\; (x_1:T_1, \ldots, x_n:T_n)</math>,

| |

| − | CVC4 adds to the context a number of instances of the formula,

| |

| − | with the goal of using them to prove the query <math>F</math> valid.

| |

| − | An instance is obtained by replacing each <math>x_i</math> with a ground term

| |

| − | of the same type occurring in one of the formulas in the context,

| |

| − | and dropping the universal quantifier.

| |

| − | If <math>x_i</math> occurs in a pattern

| |

| − | <math>\mathrm{PATTERN}\; (t_1, \ldots, t_m)</math> for the quantifier,

| |

| − | it will be instantiated only with terms obtained by simultaneously matching

| |

| − | all the terms in the pattern against ground terms in the current context

| |

| − | <math>\Gamma</math>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Specifically, the matching process produces one or more substitutions

| |

| − | <math>\sigma</math> for the variables in <math>(t_1, \ldots, t_m)</math>

| |

| − | which satisfy the following invariant:

| |

| − | for each <math>i = 1, \ldots, m</math>, <math>\sigma(t_i)</math> is

| |

| − | a ground term and there is a ground term <math>s_i</math> in <math>\Gamma</math>

| |

| − | such that <math>\Gamma \models_T \sigma(t_i) = s_i</math>.

| |

| − | The variables of <math>(x_1:T_1, \ldots, x_n:T_n)</math> that occur

| |

| − | in the pattern are instantiated only with those substitutions

| |

| − | (while any remaining variables are instantiated arbitrarily).

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The Skolemized version or the added instances of a context formula may themselves

| |

| − | start with a quantifier.

| |

| − | The same instantiation process is applied to them too, recursively.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Note that the matching mechanism is not limited to syntactic matching

| |

| − | but is modulo the equations asserted in the context.

| |

| − | Because of decidability and/or efficiency limitations, the matching process

| |

| − | is not exhaustive.

| |

| − | CVC4 will typically miss some substitutions that satisfy the invariant above.

| |

| − | As a consequence, it might fail to prove the validity of the query formula

| |

| − | <math>F</math>, which makes CVC4 incomplete for contexts containing

| |

| − | quantified formulas.

| |

| − | It should be noted though that exhaustive matching, which can be achieved

| |

| − | simply by not specifying any patterns, does not yield completeness anyway

| |

| − | since the instantiation of universal variables is still restricted

| |

| − | to just the ground terms in the context,

| |

| − | whereas in general additional ground terms might be needed.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <!--

| |

| − | == Subtypes ==

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Subtype Checking ===

| |

| − | -->

| |

| | | | |

| | =CVC4's support for the SMT-LIB language= | | =CVC4's support for the SMT-LIB language= |

This manual includes lots of information about how to use CVC4.

It is a work in-progress.

CVC4 is the last of a long line of SMT solvers that started with SVC and includes CVC, CVC-Lite and CVC3.

Technically, it is an automated validity checker for a many-sorted (i.e., typed) first-order logic with built-in theories.

The current built-in theories are the theories of:

The difference is that a counter-model is given as a set of equations providing a concrete assignment of values for the free symbols in  and

and  (see the section on CVC4's native input language for more details).

(see the section on CVC4's native input language for more details).

Once installed, the CVC4 driver binary ("cvc4") can be executed to directly enter into interactive mode:

CVC4 has various levels of verbosity. By default, CVC4 is pretty quiet, only reporting serious warnings and notices. If you're curious about what it's doing, you can pass CVC4 the -v option:

Internally, verbosity is just an integer value. It starts at 0, and with every -v on the command line it is incremented; with every -q, decremented. It can also be set directly. From CVC language:

Many statistics name-value pairs follow, one comma-separated pair per line.

QUERY asks a validity question, and CHECK-SAT a satisfiability question, and these are dual problems; hence the terminology is different, but really "sat" and "invalid" are the same internally, as are "unsat" and "valid":

Most "normal errors" return a 1 as the exit code, but out of memory conditions, and others, can produce different exit codes. In interactive mode, parse errors are ignored and the next line read; so in interactive mode, you may see an exit code of 0 even in the presence of such an error.

In SMT-LIB mode, an SMT-LIB command script that sets its status via "set-info :status" also affects the exit code. So, for instance, the following SMT-LIB script returns an exit code of 10 even though it contains no "check-sat" command:

Without the "set-info," it would have returned an exit code of 0.

Every effort has been made to make CVC4 compliant with the SMT-LIB 2.0

standard (http://smtlib.org/). However, when parsing SMT-LIB input,

certain default settings don't match what is stated in the official

standard. To make CVC4 adhere more strictly to the standard, use the

"--smtlib" command-line option. Even with this setting, CVC4 is

somewhat lenient; some non-conforming input may still be parsed and

processed.

Type Correctness Conditions (TCCs), and the checking of such, are not

supported by CVC4 1.0. Thus, a function defined only on integers can be

applied to REAL (as INT is a subtype of REAL), and CVC4 will not complain,

but may produce strange results. For example:

CVC3 can be used to produce TCCs for this input (with the +dump-tcc option).

The TCC can be checked by CVC3 or another solver. (CVC3 can also check

TCCs while solving with +tcc.)

The native language of all solvers in the CVC family, referred to as the

"presentation language," has undergone some revisions for CVC4. The

most notable is that CVC4 does _not_ add counterexample assertions to

the current assertion set after a SAT/INVALID result. For example:

Here, CVC4 responds "invalid" to the second and third queries, because

each has a counterexample (x=2 is a counterexample to the first, and

x=1 is a counterexample to the second). However, CVC3 will respond

with "valid" to one of these two, as the first query (the CHECKSAT)

had the side-effect of locking CVC3 into one of the two cases; the

later queries are effectively querying the counterexample that was

found by the first. CVC4 removes this side-effect of the CHECKSAT and

QUERY commands.

CVC4 supports rational literals (of type REAL) in decimal; CVC3 did not

support decimals.

CVC4 does not have support for the IS_INTEGER predicate.

Statistics can be dumped on exit (both normal and abnormal exits) with

the --statistics command line option.

CVC4 can be made to self-timeout after a given number of milliseconds.

Use the --tlimit command line option to limit the entire run of

CVC4, or use --tlimit-per to limit each individual query separately.

Preprocessing time is not counted by the time limit, so for some large

inputs which require aggressive preprocessing, you may notice that

--tlimit does not work very well. If you suspect this might be the

case, you can use "-vv" (double verbosity) to see what CVC4 is doing.

Time-limited runs are not deterministic; two consecutive runs with the

same time limit might produce different results (i.e., one may time out

and responds with "unknown", while the other completes and provides an

answer). To ensure that results are reproducible, use --rlimit or

--rlimit-per. These options take a "resource count" (presently, based on

the number of SAT conflicts) that limits the search time. A word of

caution, though: there is no guarantee that runs of different versions of

CVC4 or of different builds of CVC4 (e.g., two CVC4 binaries with different

features enabled, or for different architectures) will interpret the resource

count in the same manner.

CVC4 does not presently have a way to limit its memory use; you may opt

to run it from a shell after using "ulimit" to limit the size of the

heap.

CVC4 1.0 has limited support for proofs, and they are disabled by default.

(Run the configure script with --enable-proof to enable proofs). Proofs

are exported in LFSC format and are limited to the propositional backbone

of the discovered proof (theory lemmas are stated without proof in this

release).

If enabled at configure-time (./configure --with-portfolio), a second

CVC4 binary will be produced ("pcvc4"). This binary has support for

running multiple instances of CVC4 in different threads. Use --threads=N

to specify the number of threads, and use --thread0="options for thread 0"

--thread1="options for thread 1", etc., to specify a configuration for the

threads. Lemmas are *not* shared between the threads by default; to adjust

this, use the --filter-lemma-length=N option to share lemmas of N literals

(or smaller). (Some lemmas are ineligible for sharing because they include

literals that are "local" to one thread.)

Currently, the portfolio **does not work** with quantifiers or with

the theory of inductive datatypes. These limitations will be addressed

in a future release.

For a suggestion of editing CVC4 source code with emacs, see the file

contrib/editing-with-emacs. For a CVC language mode (the native input

language for CVC4), see contrib/cvc-mode.el.

is valid in the built-in theories under a given set

is valid in the built-in theories under a given set  of assumptions, a context.

More precisely, it checks whether

of assumptions, a context.

More precisely, it checks whether

is a logical consequence in

is a logical consequence in  of the set of formulas

of the set of formulas  , where

, where  is the union of CVC4's built-in theories.

is the union of CVC4's built-in theories.

is a universal formula and

is a universal formula and  is a set of existential formulas (i.e., when

is a set of existential formulas (i.e., when  and

and  contain at most universal, respectively existential, quantifiers), CVC4 is a decision procedure:

it is guaranteed (modulo bugs and memory limits) to return a correct "valid" or "invalid" answer eventually.

In all other cases, CVC4 is deductively sound but incomplete:

it will never say that an invalid formula is valid,

but it may either never return or give up and return "unknown" for some formulas.

contain at most universal, respectively existential, quantifiers), CVC4 is a decision procedure:

it is guaranteed (modulo bugs and memory limits) to return a correct "valid" or "invalid" answer eventually.

In all other cases, CVC4 is deductively sound but incomplete:

it will never say that an invalid formula is valid,

but it may either never return or give up and return "unknown" for some formulas.

under a context

under a context  it provides no evidence to back its claim.

Future versions will also return a proof certificate,

a formal proof that

it provides no evidence to back its claim.

Future versions will also return a proof certificate,

a formal proof that  for some subset

for some subset  of

of  .

.

's validity under the context

's validity under the context  and a counter-model.

Both a counter-example and a counter-model are a set

and a counter-model.

Both a counter-example and a counter-model are a set  of additional formulas consistent with

of additional formulas consistent with  in

in  , but entailing the negation of

, but entailing the negation of  .

Formally:

.

Formally:

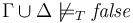

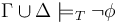

and

and

.

.

and

and  (see the section on CVC4's native input language for more details).

(see the section on CVC4's native input language for more details).